You're asking the wrong question

I didn't choose to self publish, and neither will you. I made a different choice, one most writers fail to understand, and it changed everything for me.

This article was originally published on Sub Club.

Hi,

In my long and (relatively) storied career, I’ve written over 40 novels, 16 non-fiction books, and a bajillion articles. I’ve signed over 50 publishing contracts, written for a ton of magazines, and edited several anthologies.

I’ve also worked with hundreds, maybe thousands, of writers. The newer among them often ask me some variation of “Why did you choose to self-publish so much of your work?” to which I reply with some variation of “I didn’t choose to self-publish. I chose to publish”. That nuance is a subtle, but really important distinction, because it fundamentally changes how most authors should think about their career.

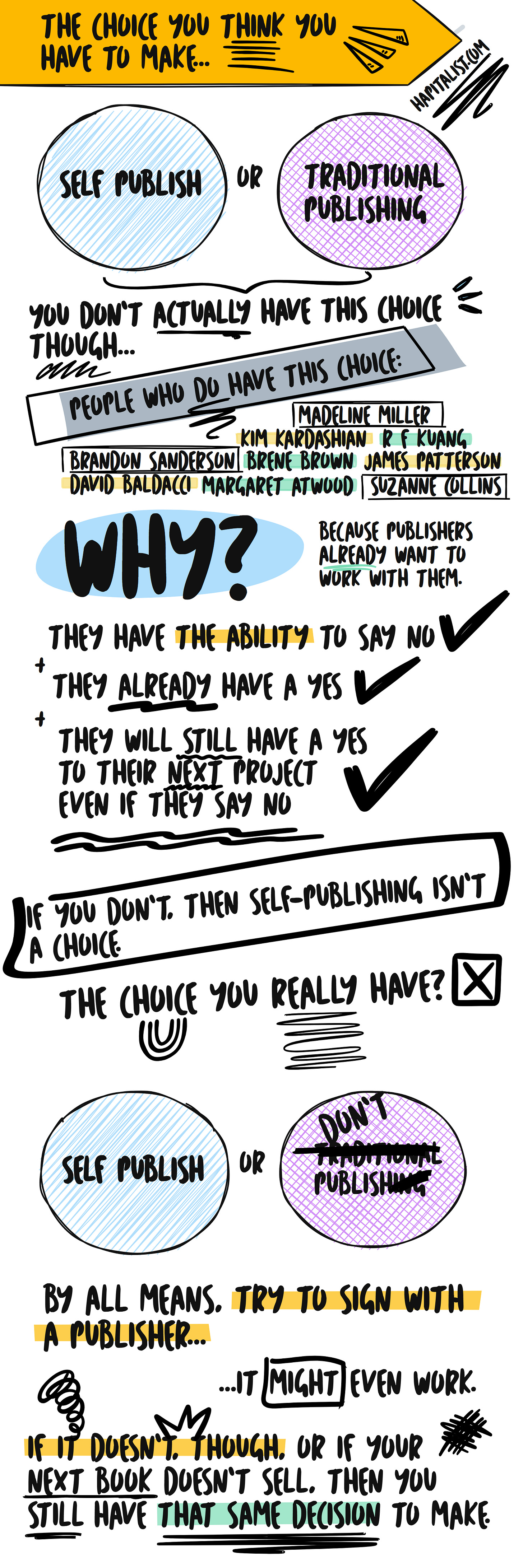

In order to have a choice in how you publish, one needs to be given the option to publish with a publisher or self-publish, and most writers, especially ones starting out, don’t have the option…because nobody ever offers them a publishing contract.

For the vast majority of authors, their choice is really between publishing at all or keeping their books on a shelf, not between traditional publishing and self-publishing.

The odds are ridiculously stacked against you getting any publishing contract, let alone one that plucks you from obscurity and gives you a career. Every year, publishers receive tens of thousands of potential projects, and only accept a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of them.

Let’s look at the numbers.

Simon and Shuster publishes roughly 2,000 books a year, out of 4 million total books that are published a year. Combined with the other “Big 5 publishers” HarperCollins (10,000), Hachette (2,100), Macmillan Publishers (250), and Penguin Random House (15,000), they publish around 30,000 total books every year.

Yes, you might get a deal, and it might be significant, and it might be a breakthrough hit, and it might change your life, but those are a lot of mights, and even publishers are frightening bad at predicting which book with break out and blow up.

Meanwhile, you can always choose yourself.

This publication has 45,000 subscribers…which means the number of people who received this email is significantly higher than the number of Big 5 titles that are published every year.

Plus, that 30,000 number also includes established authors and celebrities and reprints, leaving vanishingly few chances for you and your book.

On top of that, there are lots of amazing small presses, independent publishers, university presses, and other great outlets, but they also provide very small, if any, advances, at least until you prove you can sell. If you dream of quitting your job to stare at a lake all day pecking away on your typewriter, those kinds of advances almost never happen with small presses.

Not that they happen at bigger presses, either. The average advance these days is only $5,000-$10,000 spread out over 3-4 payments across the delivery and launch of your book. Even if you were to get a $100,000+ deal, after taking out agent, lawyer, and publicist fees, then parsing the rest out over two years, sure it’s a decent “salary”, but unless you earn out of your advance that money will dry up pretty soon.

And it is an advance, remember, which means advance against royalties. The publisher is advancing you the money they think the book will earn, and then expecting to recoup that money before they pay you another dollar.

Somewhere around 80% of books don’t earn out their advance, and publishers aren’t likely to give you another contract if your books don’t prove to be a money-earner for them…

…which is all to say that even if you get one of those life-changing deals, it might go badly, or at least underperform your expectations. If your expectation is to be plucked like a rose and become the “it writer”, then it will almost certainly underperform that.

I felt very lucky in my early career to be offered publishing contracts for a couple of my books through small presses, and I very quickly watched them bastardize the releases and luff off any responsibility. My self-publishing career started because I had to buy the rights back to my work and release them myself.

That was a choice, but the choice wasn’t really between traditional publishing and self-publishing. It was between incompetence and competence. I took those books back because, and I quote my past self here, "if somebody was going to mess up my books, it might as well be me.”

Frankly, even if you get a publishing deal, you might find that your publisher cancels your contract before the end of it, or your agent might drop you, or your hot series could fizzle, meaning you won’t have another chance at a contract, at least not in your chosen genre.

If that happens to you, then you also won’t have a choice or, more accurately, you will have a different choice. It will be the choice almost all of us come to at one point in our careers; the choice between publishing or letting your manuscript gather dust.

Only a select few of us have a real choice between traditional publishing and self-publishing .

Brandon Sanderson has that choice. Marissa Meyer has a choice. N.K. Jemison has a choice. They have the choice because publishers actively want to work with them because they actively sell a lot of books.

They can negotiate, be picky, and choose to do things any way they choose. In order to have a choice you have to actually have a choice. The choice most of us have is between self publishing or not publishing at all. When it comes to publishing, I choose to publish every time.

I’ve signed dozens of publishing deals, so sometimes that choice brings me directly into working with a traditional publisher.

Not usually, though, especially at the beginning of my career. It took a long time for me to learn how to write in a way that could benefit a select group of publisher.

Now, after doing this for 15 years, I know the kinds of books I like to write, the kinds of covers that work for me, the kinds of things my audience resonates with enough to buy, and the kinds of things that work on the mass market.

I also know how to work with and talk to publishers in their language and explain myself in a way that makes me an asset instead of a question mark.

When I write for publishers I do things a lot differently than when I write for myself because I know publishers need to attract enough readers to make our collaboration worthwhile. I need to deliver 10x value for them, and my weird portal fantasy treatises on late stage capitalism just don’t move the needle with publishers because they won’t reach a large enough audience.

That makes it a bad bet for them. They work for me, though, because my needs are a lot smaller. I only need to do 10% as well to get a good result, which is markedly easier for me than for them.

Even then, I only release one of those books when I can afford to barely break even on them.

The best experiences I have with publishers is when they hire me to write on an existing property where there’s an established market, voice, and legacy to guide me.

It works because I can write quickly without oversight and deliver clean copy that publishers can use without much editing or direction. I proactively have good ideas and execute on them without needing handholding. I understand the publishing industry on a deep level and can extrapolate from known data to synthesize why a publisher makes one decision or moves in one direction, and I don’t have deep feelings about making edits, especially if you are paying me.

All of those skills came from making the choice to publish myself, to learn publishing, and to love every aspect of publishing, even the parts I hate.

You always have that choice. You always have the choice to choose yourself. You always have the choice to pick your book off the shelf and publish it. You always have the choice to go your own way and do your own thing.

Eventually, if you make that choice, and you build an audience, people will come around, and even if they don’t, it won’t matter, because you don’t need them anyway.

What do you think?

Have you ever considered self-publishing? If so, what factors influenced your decision? If not, what holds you back from choosing that path?

What do you think is the biggest misconception about traditional publishing, and how has this article changed or reinforced your perspective?

If you could choose complete creative control over your book’s release or the backing of a major publisher, which would you prefer and why?

Let us know in the comments.

A great reality check and real insight for new authors!

your quote, " my weird portal fantasy treatises on late stage capitalism just don’t move the needle with publishers" made me ROTFL!

Hi, I plan to upgrade but I am curious what unicorn is? I don’t see that payment plan described anywhere and maybe it’s kind of a joke that I just missed, that would be embarrassing. Or is there something included with that which in not in your upgrade to the paid plan?