Animal School

The power of finding your thing, obsessing over it, and accepting the tradeoffs

Hi,

The first time I saw a post by Jonathan Goodman I reached out to see if I could interview him. He said no because his focus is on writing, and not speaking. “A funny thing happens when you become successful doing something.” He said. “The world tends to conspire to pay you lots of money to do everything but that thing.”

I laughed. He continued. “I don’t want to be a speaker. I want to be a writer.”

He told me that he was about to release a book with HarperCollins called Unhinged Habits and that he built a Substack called Diary of a Book Launch as a way to both hold him accountable and attract other writers and authors into his orbit.

Then he sent me the book, and I loved it.

It’s fascinating to watch Jonathan, who has made over $40 million selling products and services online as an entrepreneur, deploy the same methods into launching a book.

Since I’m very interested in this kind of thing, I asked if he’d write for us. He said yes, and asked if he could share the animal school story from his book, which is officially out this week.

Here’s Jon:

Animal School

A rabbit, a fish, a bird, a squirrel, and a bunch ofother animals start a school.

Arguments began when they sat down to write the curriculum. Rabbit wanted running to be included; fish wanted swimming; bird wanted flying; and the squirrel insisted there be a class on advanced tree-climbing techniques.

To appease the group, a well-intentioned mediator added each animal’s specialty into the programming. Then they made the mistake of insisting that all animals take all classes.

The rabbit cruised through the running lessons, but the instructors said it was good intellectual and emotional discipline for it to also take flying lessons. So the rabbit did what it was told, climbed up onto a ledge, and jumped off, flapping its arms just as it was taught.

The poor thing fell and broke a leg. It could never fly, but now it can’t run well either. Instead of getting an A+ in running, it got a C.

The fish had a similar experience. It did well in the swimming class. But then it was time for vertical tree climbing... and, well, you can guess how that went. The teachers gave the fish a D in climbing (because the fish asserted itself), but it had become dehydrated in the process and lost all motivation to swim, receiving a C-.

At the end of the year, the valedictorian of the class was an intellectually disabled salamander.

English came naturally to me in high school. All A’s. Math, on the other hand, was a struggle. Solid C’s. In order for me to get accepted into a good university, my average needed to improve. My parents got me a math tutor.

What happened next was a real-life version of animal school. Math, a subject I showed no natural aptitude for, became the focus. English got ignored because I was already good at it. The strategy worked. I got into a good university.

But does any of this make sense?

I don’t think so.

I should have had an English tutor, perhaps a writing coach.

You may be a genius. You may be a great writer. But you can’t get into a university unless you can also figure out the cos angle of a triangle. That makes no sense.

Growing up, external validations in the way of grades—averaged out across a wide array of opposing aptitudes—are what you’re judged on. But then you get into the real world, and it doesn’t matter if a rabbit can fly, because the rabbit’s fast. And fish don’t need to climb trees; they swim.

You have a thing. A thing that comes natural to you. A thing that you just seem to get. Where you wonder why, even if it’s hard, you have boundless energy for it. A thing that makes sense to you in a way that disables you from having conversations with people you know about it because it’s so clear to you, and foreign to them.

How do you know what your thing is? Here’s a three-part test:

What seems easy to you, yet hard for others?

What do you have boundless energy for?

What can you consume an unlimited amount of content about?

Once you find your thing, obsess over it. Accept the tradeoff that nothing you could work on matters as much as it does.

I write every morning for two hours before my family wakes up. I don’t like to wake up early. But early morning is when my brain works best. So I wake up early.

Waking up early is a constraint (like packing a small backpack for a trip) that has downstream effects on the rest of my life.

Because I wake up early, I go to bed early. I don’t drink alcohol because it wrecks my sleep. I rarely accept invites to social events at night or attend concerts because they end late.

I’d love to see more live music. But I’m not willing to sacrifice my writing for it. I’ve also turned down advisory board invitations. In order to maximize, you must minimize. Identify the tradeoffs. Accept them gladly.

I don’t read a lot of books on writing, but I do read a lot. And everything I read, I read with the goal of improving my writing. I wish I could read for pure pleasure. I’m simply unable.

Whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, I’m studying. The title of the introduction of my previous book The Obvious Choice is “Business Was Great, Once.” The first line of Elantris by Brandon Sanderson is “Elantris was beautiful, once.”

I’ll steal like an artist, stealing that phrase from Austin Kleon. For example, “He’s the type of guy who wears a bike helmet while grocery shopping.” I didn’t come up with that. I don’t quite know what it means. But it’s great. I’ll use a version of it somewhere at some point, probably.

The primary goal of my social media is to test passages and use the feedback I get there to improve them.

Everybody’s got a thing. Most never pursue it fully and therefore never thrive. “Bring up your average,” you’re told. Fly, if you’re a fast runner. Climb, if you’re a good swimmer.

Being average isn’t fun. If you follow that path, your energy will ebb and flow: feeling motivated for brief periods before burning out again.

Burning out isn’t the result of working too hard for too long. It happens when you work on the wrong things, or too many things.

You’ve got your thing. You know what it is. The more you design everything else you do to maximize it, the better. The less of everything else, the better.

There’s nuance to this conversation though. A but.

The corollary to the animal school parable is that mastery over one thing is great and fun and absolutely something to go after. But if you want to be conventionally successful with it, your thing needs to be supported by a mediocre-to-just-okay level in what I call “Leapfrog Skills.”

Leapfrog Skills are transferable. They can be combined with any industry expertise to make you more valuable. With them, you’ll have an advantage in any entrepreneurial venture or become indispensable to your employer, allowing you to command a higher salary. If you change industries, you’ll take them with you.

The five biggest Leapfrog Skills are:

Business writing: Get to the point. Hook the reader. Tell a story. Write simply. Offer an actionable takeaway.

Behavioral psychology: Recognize, navigate, and take ethical advantage of the major cognitive biases.

Conversation: Ask the types of questions that encourage others to talk about themselves.

Sales: You get what you want by helping others get what they want.

Wealth management: Make money with money. With patience, even a little bit of money is enough money to make meaningful money.

The following is a good guideline for how the most successful people in their fields focus their professional development over time:

Year 1: 75% industry skills / 25% Leapfrog Skills

Year 2: 50% industry skills / 50% Leapfrog Skills

Year 3 onward: 25% industry skills / 75% Leapfrog Skills

Industries have different baseline levels of knowledge required for results. Your ratio might be different, but even if it is, it’s probably not by much.

Focus is the key to skill acquisition in a world determined to distract us. Nothing’s new about that advice. You hear it all the time. “The art of focus.” “The secret to success is to be more focused,” they say. Well, how do you decide on your focus? Then, how do you stay focused?

Leapfrog Learning has two parts:

Sixty-day focused sprints

Teach

The best way to stack skills is to choose one at a time and focus for sixty days of dedicated effort.

Why sixty days?

It’s long enough to develop a mediocre level of skill yet short enough to feel doable.

Once you learn a skill, having it becomes your new normal. Like building muscles or riding a bike, if you don’t use it for a while it’ll get rusty but come back quickly.

Now onto the second part of Leapfrog Learning: teaching it.

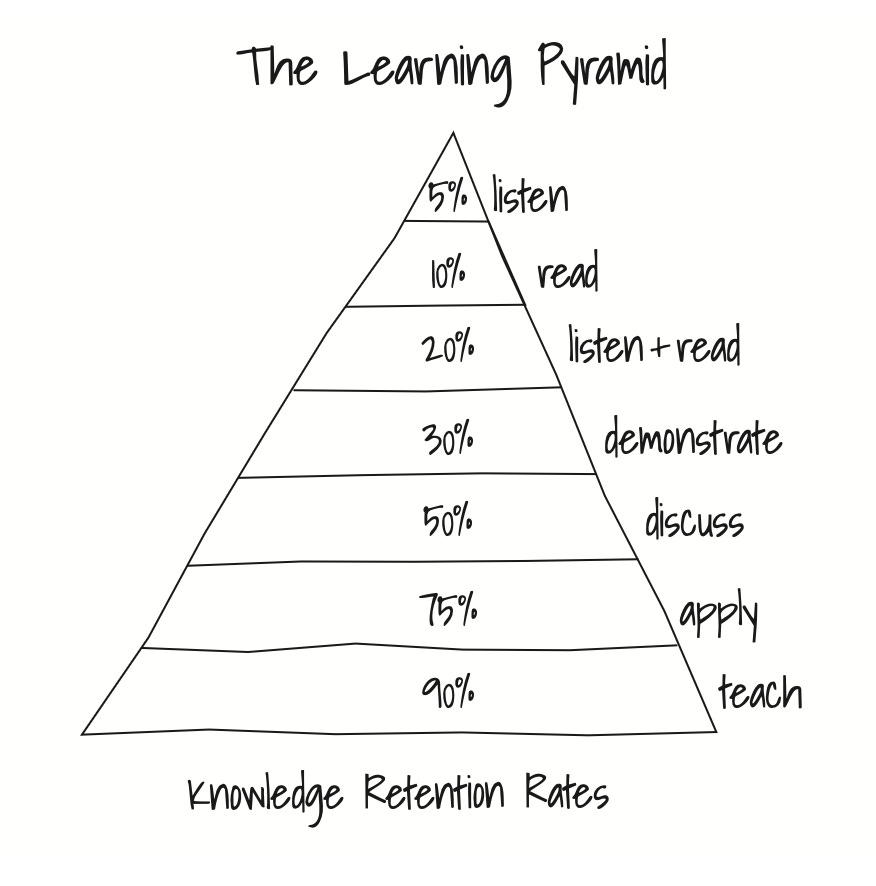

A lot of work these days includes listening and reading. That’s where most people stop.

Teaching helps you retain more than 90% of what you’re learning as opposed to listening and reading, which generally sits around 20% knowledge retention rates. These numbers aren’t scientific. Whether they’re technically accurate or not isn’t as important as the pattern: Teaching is the best way to learn and retain what you learn.

Here’s three examples of Leapfrog Learning:

Get better at social media by choosing one platform to master, listening to podcasts, reading blog posts, and studying the top accounts. After sixty days, build a slide deck, invite three friends over, feed them pizza (without pineapple—pineapple on pizza is gross), and present what you’ve learned.

Build your personal wealth management philosophy by studying topics like greed and envy, interviewing financial advisors, reading books about investing, and listening to case studies where knowledgeable people share honestly what they do with their own money. After sixty days, teach a loved one about your philosophy or record a podcast episode about it.

Figure out what to do about artificial intelligence by reading books and listening to experts speak about how it’s going to redefine job roles in the future. Once done, compile a report for your industry and send it to five colleagues.

What’s useful about focus is that a little bit goes a long way. Every time you do a leapfrog period, you’ll find yourself not just a little bit ahead of where you were previously, but a lot.

Look at the unspoken assumptions in your field. The “must-dos” that everyone accepts as gospel.

Most aren’t universal or mandatory.

Find the true top performers. They’re not doing everything. They’ve identified the vital few things that matter and become exceptional at those while merely appearing competent at the rest.

Basic arithmetic undoubtedly matters. But beyond a certain point, if a person isn’t going to go into a career that requires complex mathematics, its importance falls off a cliff.

Specialization isn’t limitation. It’s leverage. The more focused your energy, the more impact you create.

Yes, this is unhinged. However, I tend to think that’s a good word.

-Jon

--

Jonathan Goodman is the author of the newly released Unhinged Habits: A Counterintuitive Guide for Humans to Have More by Doing Less. It’s full of helpful frameworks to break bad habits and build your rich life by mastering the art of strategic subtraction.

If you liked Atomic Habits or Essentialism, you’ll love this book. Same lane, but a contrarian spin with more focus on the deeper values of relationships, health, and purpose.

Unhinged Habits is a practical and philosophical examination of why modern success feels so exhausting—and how to step out of the middle. Rather than promoting discipline, optimization, or hustle, Jonathan Goodman argues that lasting change comes from designing habits, environments, and expectations that reflect how people actually live.

Written for those who are busy, capable, and quietly dissatisfied, the book offers a framework for doing less, choosing deliberately, and designing a life you don’t need to escape from.

These are the core ideas explored in Unhinged Habits and Jonathan Goodman’s work:

Strategic Subtraction: Why doing less—intentionally—is often the fastest path to clarity, momentum, and sustainability.

Getting Out of the Middle: The hidden cost of indecision, half-commitment, and chasing conflicting definitions of success.

Building for Humans, Not Algorithms: How trust, specificity, and consistency outperform visibility and optimization over time.

Redefining Success: Designing personal metrics that reflect values rather than social comparison.

Habits as Alignment, Not Discipline: Why consistency emerges naturally when habits fit real life.

You did it. You convinced me I should read Unhinged Habits.